Centre

for Dominican Studies of Dacia

Centre

for Dominican Studies of Dacia

Centre

for Dominican Studies of Dacia

Centre

for Dominican Studies of Dacia

The Dominican priory and convent

of medieval Roskilde, Denmark

by Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen (2005)

Slightly edited web-version of article in ‘Dominican History Newsletter’ vol. 14 (2005), pp. 257-278.

Link to printable PDF-version.

The city of Roskilde is situated on the central part of Zealand, which is the biggest of the Danish isles. It was founded in the middle of the tenth century as a new main seat of the Danish kings. The town also became seat of the bishops of Zealand, who are known from the beginning of the eleventh century. In ecclesiastical matters, Roskilde became the vice-capital of Denmark, only second to the archiepiscopal centre of Lund, with more than 20 churches by the end of the Middle Ages. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, Roskilde housed a cathedral and a secular chapter of canons, and a nunnery of first Benedictine, later Cistercian observance. The Dominican friars arrived in 1231, and were soon followed by Franciscan friars in 1237. A Franciscan nunnery is known from 1255, while the first of only four Dominican nunneries in medieval Scandinavia was founded in Roskilde in 1263.

The first Dominican friars arrived in Roskilde in 1231, where a convent was founded in 1234.[1] Our knowledge on this and several other early Dominican events in Denmark is based on a Roskilde Franciscan Petrus Olavi and his chronicle written in 1533-34.[2] The official founder of the Roskilde convent is unknown, but quite a significant contribution to the financing was given by Johannes Ebbesen, the king’s marshal, who donated 40 marks silver to the building of a priory and a priory church, before he died on the crusade in 1232.[3] According to our Franciscan chronicler, the church of the Friars Preachers in Roskilde was consecrated in 1254 and dedicated to St. Catherine.[4]

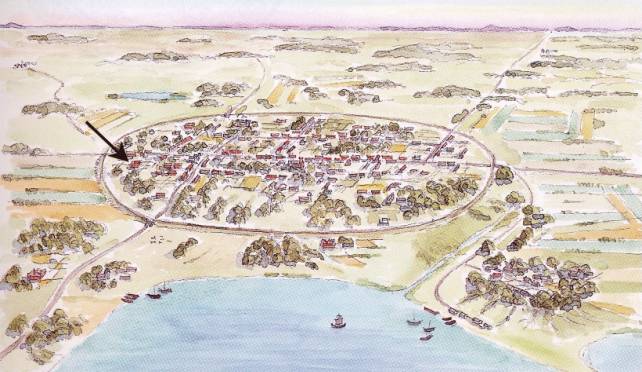

Reconstructed prospect of Roskilde anno 1275 seen from the north (over the fiord). The cathedral is situated in the centre of the city, while the inserted arrow points to the location of the Dominican priory, of which the actual building-construction is unknown. Drawing by Mogens Suhr Andersen in Birkebæk et al. 1992, 231.

The priory of the Friars Preachers in medieval Roskilde

The Dominican priory was built in the north-eastern part if the city. Nothing is preserved from the medieval complex, which is believed to have been situated a bit further north west than the present-day “monastery”, Roskilde Kloster, a former Lutheran home for unmarried ladies of rank, built on the site in the late sixteenth century. The priory site has never been investigated systematically by archaeologists, but traces of graves and remnants of buildings have come to light during the last century, as diggings have been performed in relation to road constructions and other building activity. While the supposed site of the main buildings remains almost untouched for future archaeologists, an area to the immediate east of the priory has shown some interesting remnants, e.g. a tile kiln, a stone cellar, and several parts of the surrounding outer wall. Still, on the whole, very little is known about the appearance of the Roskilde priory.

The written sources do not provide much help in this regard. They only confirm that the priory did indeed have a church, which as already noted was consecrated in 1254, while significant donations of money were given in the 1330s and 1350 for repairs on both the church and the rest of the priory.[5] Furthermore, from a letter of 1453, we learn about an important meeting, which took place in the chambers of the Roskilde prior.[6]

The written accounts do, however, give some information about the exterior surroundings of the priory. By the Reformation, the priory site seems to have covered an area of more than 2 hectares, and thereby made up a significant part of the north-eastern corner of the town. Strangely enough, though, the site does not appear to have been in direct contact with any of the major streets of the town. According to a description of the area in 1538, the main street of the city, Algade, was situated about 40 to 50 metres to the south of the southern priory wall, while the exit road leading to the north ran at a similar distance to the west of the site.[7] From both of these busy roads, where land traffic from eastern Zealand (with Copenhagen) and north-eastern Zealand respectively met with the rest of the island, small alleys led into the supposed location of the priory. The western alley is still called Munkebro (“Pavement of the Monks”), while the southern alley leading to main-street Algade may have had the name Klosterstræde (“Cloister Lane”). If we may compare with other mendicant priories in medieval Scandinavia, it is quite possible that the intersection of the two alleys constituted a small square in front of - or very close to - the western gable end of the priory church. Also, since all known priory complexes of both Dominicans and Franciscans in Denmark follow a general practice that the priory church always was located as close to the main streets as possible, the situation in Roskilde would suggest that the church constituted the southern wing of the priory. To the immediate north of the alleged “Friars Preacher’s Square”, we could expect the southern gable of a western priory wing - if indeed the priory had such a wing. This is, however, mere speculation.

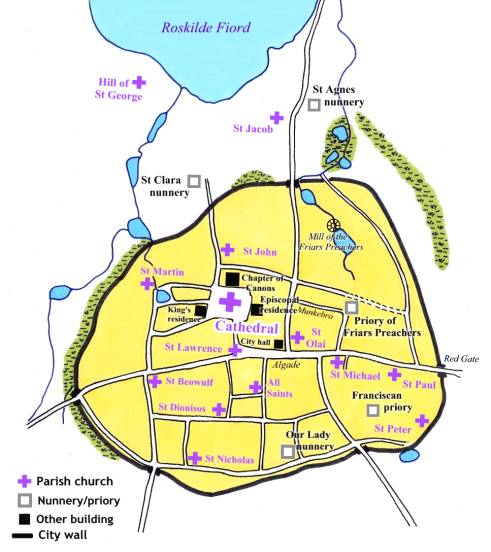

Reconstruction of the city plan of late medieval Roskilde. The exact course of the minor alleys and the position of some of the parish churches are uncertain. Based on earlier maps by Fang 1945, 27, and Birkebæk et al. 1992.

What we do know is that the friars held a large area north of the priory, probably both inside and outside the city wall, where the terrain slopes rather steeply towards the fiord. In this area, one of Roskilde’s many springs (the suffix word -kilde in ‘Roskilde’ actually means “spring”) come to surface, and through damming, this small stream formed several ponds with enough power to work a number of water mills on its way to the fiord. The first of these was the Mill of the Friars Preachers (molendinum fratrum predicatorum), which is mentioned from 1329 onwards.

The physical origin of the Dominican priory in Roskilde may be found a little east of the mill (and hence north east of the priory itself), as a document concerning a purchase by the friars of a neighbouring site in 1441 describes that this new site stretched »..to Munkægabet (“Monk’s Gap”), which is lying by our tile barn.«[8] This ‘tile barn’ most likely constituted a combined brickworks and storage facility for the bricks and tiles used for the building and maintenance of the priory. In addition, it is not unlikely that bricks were sold to non-Dominican building projects outside the priory.[9] In the 1970s, archaeologists found a medieval tile kiln on the priory site to the east of the supposed location of the main buildings. The kiln must have been used for a longer period, as it appears to have gone through several major reconstructions. The place-name “Monk’s Gap” has never been formally explained, but one can guess that it represents popular humour as a local name for the adjoining clay pit of the friars.

Within the priory walls, the Roskilde Dominicans are known to have had a garden. Both a garden and a garden wall are mentioned with some importance in 1543, when the king began to sell out the confiscated priory site.[10] Even more informative is a letter from 1380, which speaks of an apple orchard of the Roskilde friars (pomerio fratrum predicatorum Roskildis), and thus at least a part of the Dominican garden must have been used for fruit trees.[11] As with the brickworks, the friars’ cultivation of fruit might be ascribed a role that stretched beyond the priory walls. The above-mentioned study of the Nordic Franciscans indicates that mendicant gardening may indeed have set a precedent for Scandinavian horticulture, just as the Cistercians are often - with or without cause - ascribed the honour of several agricultural innovations in Scandinavia.[12] In any case, it is fair to assume that in years with good harvests also the local community had the opportunity to buy and enjoy Dominican apples.

Approximately one kilometre north of the priory, outside the city wall, a Dominican nunnery was founded in 1263.[13] While this nunnery received huge estates all over Zealand and in the proximity of Roskilde, it is uncertain whether the Roskilde friars also held land outside the priory wall. Such a practice was not common among Dominican convents in Denmark, and the medieval sources do not speak of any such landed property in Roskilde either, but in a deed from 1584, the Crown sold »..a deserted plot of land at Roskilde, which from time immemorial belonged to Blackfriar Priory, and on which the ladegård of Blackfriar Priory has stood.«[14] The Danish word ladegård (“barn farm”) can bear several meanings, as for instance many royal castles had their manors driven from such ladegårde, and ladegård is also the Danish word used for the well-known Cistercian granges. Does this mean that the Dominican friars in Roskilde were involved with actual agriculture - that they farmed rural land on their own? Probably not. The deed also mentions that the ladegård was situated by the eastern gate of the town (Red Gate). It is not said if it was on the outside or the inside of the wall, but in both cases, such a position more points to a possible use as an actual barn, where deliveries of grain and other rural necessities could easily be unloaded and stored - instead of using the narrow alley to the front door of the priory. Indeed, this could also be a potential place for selling any surplus production from the priory’s orchard and brickworks.

The Dominican friars in Roskilde did, however, possess at least one farm far away from the priory. During the years of dissolution, the Roskilde convent in 1532 was forced because of financial problems to sell a farm in the city of Slagelse, which is situated in south-western Zealand, 55 kilometres from Roskilde. According to the letter of sale, the farm was occupied by a friar, who took care of the preaching and collecting af alms in this part of Zealand, where there were no Dominican or Franciscan convents.[15]

The Dominican convent in medieval Roskilde

The Dominican friars of Roskilde do not have a prominent place in the town’s medieval history as it has thus far been written. Written sources on the medieval friars in Roskilde are indeed sparse, and even though my slavish review of all the published source material from medieval Denmark has identified more than a hundred references, in contrast with the ten which until now have been most commonly used, there is, alas, little that can be said about the Roskilde convent. In 1832, the same realization led to this harsh conclusion by town’s historian H. Behrmann: »This priory or, which is the same, its inmates, the Black Friars, have played such an insignificant supernumerary part at the World’s Theatre, that they are hardly ever mentioned in the annals.«[16] Here, an objection on behalf of the Dominican convent in medieval Roskilde is certainly in its place, as this convent do indeed appear to have been the most important Dominican centre in high medieval Scandinavia only second to Lund, and throughout the Late Middle Ages it held second place among the 15 convents of Denmark. When it was time to elect a new prior provincial, the provincial chapter in several cases chose the current prior in Roskilde. For example, Prior Olavus of Roskilde was chosen provincial by the chapter in Sigtuna in 1286,[17] and when he resigned in 1302, he was replaced by his successor in Roskilde, Prior Petrus.[18]

Also, the first prior provincial of Dacia, Frater Rano, came from Roskilde, although not from the convent (as his election was before its foundation) but from the cathedral chapter, where he had served as dean. This information was given on his tombstone, which according to Atlas Danicus (c.1674) was found among the ruins of Roskilde Priory in 1670. Unfortunately, the stone itself soon vanished, but the inscription is preserved in the seventeenth-century Atlas: »Hic jacet frater Rano, primus prior provincialis fratrum Prædicatorum in Dacia, quondam decanus Roschildensis.«[19] Several contemporary Dominican sources refer to Rano, who died in 1238. As prior provincial, he did not belong to any specific convent, although he probably had his ‘main office’ in Lund, but nevertheless, he chose the priory in Roskilde for his burial place. This, together with Rano’s secular background in Roskilde and the fact that the Roskilde convent was founded during his reign as provincial (1228-1238), led the major historian of Dominicans in Scandinavia, Jarl Gallén, to the likely assumption that the establishment of Friars Preachers in Roskilde in the early 1230s was partly the result of Rano’s personal choice.[20]

In the garden north west of the present Roskilde Kloster, a wooden sculpture carved out of an oak tree marks the spot where the few archaeological remnants of the medieval Dominican priory have been found. The sculpture is made by artist Ole Bülow and represents Frater Rano, the first Dominican provincial in the Nordic province of Dacia. Indeed, the statue might even serve as a sepulchral monument, as it was in this very area that Frater Rano’s tombstone was found in 1670 - but unfortunately later on was lost again. Photo in van Deurs 1999, 6.

Not only the post as prior provincial, but also other important provincial offices - such as preachers general and vice-provincials - were often held by priors and lectors from Roskilde. Together with the convents of Lund and Ribe, Roskilde is the convent in Denmark with the greatest number of known lectors (often more than one at the time), a fact which could indicate that these convents held an elevated position in the provincial school system, perhaps as so-called ‘provincial schools’, even though they are never called such. Indeed, several Roskilde friars are known to have been granted scholarships at European studia generalia and universities by the General Chapter.

Seals for two of the leading office-holders at the Dominican convent in Roskilde: the prior (left), and a personal seal for Lector Mathias Pedersen (Matheus Petri) from 1483 (right), at this time also serving as vicar provincial. Danske gejstlige Sigiller no. 446 and 447.

All these indications of a primary position among the Dacian convents are, however, somewhat inconsistent with the fact that not a single provincial chapter is known to have taken place in Roskilde. Certainly, the list of known provincial chapters in Dacia is very far from being complete, but still, the absence of Roskilde on the list is striking. Nevertheless, it must be yet another example of random transmission in the sparse written sources of the province. The Dominican convent of Roskilde should be expected to have housed several chapters - probably as often as one every ten to twenty years.[21] Actually, an indication of a possible provincial chapter held in Roskilde is given in a letter from August 1315, where the prior provincial approved of a special agreement made earlier the same year concerning the Dominican nunnery.[22] Now, the letter does not say anything about a chapter meeting, but it does state that it was written in Roskilde, and at the time of year when provincial chapters in Dacia usually were held; 1315 is one of the years with no known locality for the provincial chapter, which thus could have taken place in Roskilde.

Seal of the Dominican convent in Roskilde. Woodcut reproduction in Resen’s Atlas Danicus of 1674, 45.

We generally know very little about the background of those who entered the Order of Preachers in medieval Scandinavia. For two Roskilde friars, the sources do, however, reveal their occupation before taking the habit. Frater Bo (Boecius), one of the most prominent priors of the Roskilde convent and its leader in the 1260s, was formerly a provost at the cathedral chapter in Roskilde. This information is given in a letter from 1267, where a papal legate was in Denmark to solve a great dispute between the king and the archbishop, which had led to an interdict upon the entire kingdom. The Danish Friars Preachers, who took the side of the king in the strife, had broken this interdict several times, and therefore Prior Bo together with the prior provincial were excommunicated by the legate Guido; it is from this letter of excommunication that we learn of »Bo quondam præpositum Roskildensem.«[23] The other Roskilde friar with a known professional background also had belonged to the secular Church. Petrus Brackæ was a parish priest from Broby on rural Zealand, who according to a monastic chronicle gave all his possessions to the Cistercians in Sorø Abbey shortly after 1312, before he joined the Dominican convent in Roskilde.[24] For a local parish priest on south-western Zealand to give up his secure secular life and join a convent more than 40 kilometres away, one can imagine that Petrus at least partly had got his inspiration from visiting Roskilde friars touring the district.

Donations and donors

The extant records account for 33 donations given to the Friars Preachers in Roskilde from 1232 to 1529. The donations can be grouped in two main types, one consisting of big extraordinary donations of money given to the convent in Roskilde alone, and another consisting of smaller gifts - often from wills - where the Roskilde friars were endowed together with a number of other ecclesiastical and charitable institutions within the region.

The first recorded donation is the previosly mentioned 40 marks silver given by the king’s marshal Johannes Ebbesen for the foundation of the priory before his death during the crusade in Acre in 1232. Johannes belonged to the mighty and wealthy Hvide Family, a noble clan, which at this time owned most of Zealand and almost monopolized the episcopal office in Roskilde. The next major donation also came from the Hvide Family, namely Countess Ingerd, who is especially known as the great patroness of the Franciscans on Zealand, but her generosity also reached the Dominican friars in Roskilde: they received 20 marks denariorum and some silver objects from the countess in 1257.[25] According to the same will, the countess had promised to pay 24 marks denariorum to the Benedictine nunnery of Börringe (in Scania), and for some unknown reason this monetary transaction was to take place through the Order of Preachers. Apart from this brief notice, we have no knowledge of any relation between the Dominican friars and the nuns of Börringe. We do, however, have several indications on the Dominican role in Scandinavia as papal preachers of the crusade, and therefore it is no surprise that the countess also bequeathed our friars with 14 marks denariorum to redeem her from a crusading vow - although it may be slightly surprising that she, as an elderly woman, had taken such a vow in the first place.

The greatest patroness of the Dominican convent in Roskilde was the powerful dowager Duchess Ingeborg (1301-c.1360), who played an important part in Scandinavian politics in the first half of the fourteenth century. She was a Norwegian princess who at a very early age married a Swedish prince, whereby she became Duchess of Sweden. Indeed, she had prospects of becoming ‘Queen of Scandinavia’, as her husband had ambitions in a contemporary and dangerous game for all three crowns of the North. And when all of the kings and pretenders (including Ingeborg’s husband) suddenly died within few years around 1320, she found herself the mother of the chosen heir to the thrones of both Sweden and Norway. Since her royal son, Magnus Eriksson, was only three years old at the time, Ingeborg at first played a major role in his early years of government, but soon she was removed from both of the governing councils by the Swedish and Norwegian nobles. Instead, Ingeborg turned to her Danish properties, which included large parts of Northern Zealand that she held in mortgage with her second husband, the Duke of Halland, who together with the Counts of Holstein had deposed the Danish king and in fact now ruled the country by themselves.

During this notorious ‘Reign of the Counts’ in the 1330s, Duchess Ingeborg (from 1330 a dowager duchess for the second time) donated a total sum of 100 marks silver to the Friars Preachers in Roskilde for the repair of the priory church and for the general maintenance of the convent.[26] In 1350, times had changed significantly, as King Valdemar IV with a stern hand had regained power in Denmark and in doing so had taken most of Ingeborg’s Danish possessions. Still, the dowager duchess was no more impoverished than she was able to give another grand donation of 60 marks silver for the repair of the Dominican priory in Roskilde.[27] In point of fact, we do not know why Ingeborg felt so attached to the Friars Preachers in Roskilde (the episcopal city was not even part of her North-Zealand lien), but no other convent or monastery received any similar donations from the duchess. Even in 1358, when she had long since returned to her Swedish estates, she remembered her beloved friars in her last will and testament. While a grand part of her estates were given to the local Dominican nunnery in Skänninge, the sisters were to take 6 solidos grossorum out of the revenue each year and send it to the friars in Roskilde for them »..to keep their lamp burning in the chancel.«[28]

Besides these large donations, the Dominican friars of Roskilde are mentioned in 28 wills with bequests of more modest amounts. In this type of donations, we usually cannot claim any special preference for the Dominicans from the donors, as wills of late medieval Denmark most commonly include every monastic institution in the province or diocese. Indeed, in some cases a legacy to the Friars Preachers in Roskilde can even be interpreted in a somewhat negative way, as for instance when the neighbouring convent of Friars Minors in the same will is given a significantly larger donation. Usually, the bequests amounted from 1 to 5 marks denariorum. For the most part the bequest was given as a lump sum, but a few donations consisted of annual payments on the testator’s day of death in connection with the celebration of a requim mass in the priory church.

Apart from the silver objects given by Countess Ingerd, all recorded donations to the Dominicans in Roskilde during the thirteenth century consisted of money, but from 1299, donations of grain (barley and rye) became frequent. The gifts were normally to be handed over to the whole community, but in some cases, these collective donations were supplemented by specified gifts for individually-named brethren. For instance, Jakob Herbiornsen, a nobleman of northern Zealand in 1299 bequeathed to his personal confessor, Father Petrus of the Dominican convent in Roskilde, a hymn book, while the convent as a whole was given two solida of grain.[29] In two later wills, the convent was given a sum of money collectively, while each priest of the convent was bequeathed with a little extra if he would pray for the soul of the testator.[30]

Many of the registered donors are historically known persons, and from the context of the remaining letters, it is quite evident that practically all the benefactors of the Roskilde Dominicans belonged to the nobility - and by far the majority to lay members of the class, and with bases on Zealand. In the high medieval phase of the convent, the friars enjoyed a distinct connection to the powerful Hvide Family. Marshal Johannes Ebbesen and Countess Ingerd have already been mentioned, and in the next layer we find several noble women of the family, some of them even living in the west Danish province of Jutland. In the Late Middle Ages, the Hvides were followed by other noble families as important contributors, such as Gyldenstjerne, Göye, Lunge and Rosenkrands.

In the donation list, the secular clergy of Roskilde is represented by Bishop Jakob Poulsen in 1350 and Bishop Lage Urne in 1529, together with Canon Peder Stegh, Dean Laurids Nielsen, and Provost Otto of the cathedral chapter in 1421, 1434, and 1490 respectively.[31] To this group of donors, we can add Bishop Niels Jakobsen Ulfeldt, who founded a chapel within the cathedral (St. Laurentii Chapel). When this chapel was allocated to one of the cathedral prebends in 1402, it was decided that an annual payment of 1 solidum grossorum should be taken from the chapel and given to the local Friars Preachers for a mass on the day of the founding bishop’s death;[32] he too, incidentally, belonged to one of the leading noble families of Zealand with connections to the extensive Hvide Family.

In terms of individual donations (disregarding their size), 73 per cent of all gifts to the convent in Roskilde came from lay nobility (mainly high nobility), while 21 per cent can be ascribed to local high clergy.[33] The remaining 6 per cent represents two donors, a stablemaster working for the bishop and a man of “mixed social class” (probably both burgher and lower nobility).[34] With these two possible exceptions, the urban bourgeoisie together with the royal family is remarkably absent in the donation list of the Roskilde Preachers. In terms of gender, the donors are almost equally divided between men and women.

Friars and priory interrelating with the outside world

Six local-ecclesiastical donors out of 33 is not overwhelming for a mendicant convent situated in the second-largest ecclesiastical town in the kingdom. We can compare the record with that of Lund: of the 80 registered donations to the convent of Lund, more than half came from canons (or archbishops) of the local cathedral chapter. Also in other areas, we get the impression that relations between secular clergy and the Friars Preachers were quite different in the two major ecclesiastical cities of Denmark. Bonds seem to have been much closer in Lund than it ever was in Roskilde. It should be noted, however, that we do not have any explicit signs of bad feelings between the Preachers and the secular clergy in Roskilde, not even during the exhausting dispute in the second half of the thirteenth century between the bishops of Roskilde and Lund against the king, where the Dominican friars sided with the Crown (just as the Roskilde canons often did).

The ‘warmest period’ of secular-Dominican relationships in Roskilde can, according to the written sources, be seen as the second quarter of the fourteenth century. This was quite a dramatic period in Danish and Zealand history, as royal authority was heavily challenged and often completely disregarded by powerful Holstein and Danish land-mortgage holders. While the kingdom was falling apart, the Church was in fact the only administrative institution left to watch over the interests of the common people and to advocate a Christian behaviour from its rulers. In contrary to earlier political conflicts, Danish Dominicans - or at least the Zealand Dominicans - do not appear to have taken side in these very turbulent times where alliances more or less changed with the seasons. Instead, Roskilde’s Preachers seem to have joined forces with the leading canons of the cathedral chapter in a pragmatic attempt to make things work as well as possible within the diocese. From 1322 to 1343, local Dominicans appear four times as witnesses for the chapter or for the bishop in various cases, and this is quite extraordinary, as nothing similar is registered one single time before or after this ‘Holstein Reign’. It is probably not coincidental that the episcopal seat of Roskilde for the main part of the period in question was indeed held by a Danish Dominican, namely Frater Johannes Nyborg [1330-1344], who had served as papal penitentiary at Avignon before he was sent to Denmark in 1329 as nuncio and papal tithe collector. However, the extant letters do give the impression that the daily administration of the Zealand diocese, as well as the relations with the Friars Preachers, was for a large part handled by the leading canons of the Roskilde chapter. Undoubtedly, the alliance with the Roskilde canons turned out to be a wise one for the priors, once a revived royal power on Zealand appeared from 1341-43 with its centre in the cathedral chapter. Moreover, the leader of the canons and the new king’s supporters, Dean Jakob Poulsen, was elected Bishop of Roskilde in 1344, and was - as already mentioned - one of the very few seculars of Roskilde who endowed the Friars Preachers in his will.[35]

Indeed,

Jakob Poulsen appears as far the most favourable representative of the secular

Church in Roskilde towards the Order of Preachers in general - and vice versa.

After working closely with the Dominican friars in Roskilde both as dean and

bishop, Jakob went on a fatal journey across the Baltic Sea to the coast of

North Germany in 1350, where he became sick (perhaps by the plague?) and lived

his last days at the Dominican priory in Stralsund. The priory had a brother set

aside solely to serve the bishop, and for its hospitality, the community, with

whom he chose his burial place, was generously endowed in Jakob’s final will -

which also included every Dominican convent back home on Zealand. Furthermore,

the will informs us of a collection of Dominican sermons which the bishop had

received from a Frater Matheus - probably a Preacher from the convent of

Roskilde.[36]

Actually,

one is almost left with the impression that Jakob could have been a Friar

Preacher himself, but it is almost certain that he was not. Still, if he should

have chosen another career, he probably would have been…

In Denmark, sources are remarkably scarce concerning relations between Friars Preachers and urban guilds. This is also the case with Roskilde, where we find no evidence of bonds with any of the craft guilds of the town. A few brethren were, though, members of the Guild of St. Lucius, which had participants from all social layers of Roskilde and was led by the bishop himself. Usually, notations in the guild lists are about food, grain, and beer, as when we learn that Tue Jepsen, cook with the Friars Preachers, in 1484 was obliged to help with the feeding of the guild members.[37] It would appear as if contact to the guild mainly was taken care of by the convent’s lay brothers.

As mentioned above, the Roskilde Dominicans for a period functioned as witnesses for their secular neighbours at the cathedral chapter. More often, the priors acted as witnesses for matters outside of Roskilde. In 1265, for instance, Prior Bo attested a royal letter of privileges to the Augustinian Abbey of Æbelholt in northern Zealand,[38] but in several cases, the priors were witnessing issues of absolutely no ecclesiastical bearing at all. As in 1449, when Prior Andreas Hak attended and sealed an exchange of real estate between two noble relatives, a deal which incidentally took place at the Franciscan priory in Copenhagen.[39] In 1451, the Roskilde prior witnessed a local court ruling in northern Zealand concerning a demesne’s access to grassing areas,[40] and in 1443, the Roskilde prior put his seal under a mortgage agreement between two local magnates regarding some wading hauls in the Isefiord;[41] though I do not know exactly what a ‘wading haul’ is, I think it safe to claim that we are dealing with a concern not traditionally reckoned among Dominican pursuits. In terms of the Preachers’ social relations in the medieval community, it is interesting to note that once again we find a distinct preference for relating to the highest levels of society, all the way to the top. Especially during the third quarter of the thirteenth century, the Friars Preachers of Denmark seem closely connected to the Crown. Allegedly, they readily broke the interdict called upon the kingdom during the king’s quarrel with the archbishop and the bishop of Roskilde. As for the Dominican friars in Roskilde, a Preacher called Bo, probably the later Prior Bo of Roskilde, represented the king’s party at a peace negotiation in Lund in 1256.[42]

Also the papal curia quite often made use of Danish Dominicans, not least as collectors of papal levies. When Nuncio Petrus Gervasii was given the ungrateful task of collecting crusade tithes in Denmark during the early 1330s, when the kingless country was governed by foreign warlords, he was at first given a Danish Dominican at Avignon as his companion, Frater Johannes Nyborg. This brother was, however, shortly before their departure to Denmark in 1330 appointed bishop of Roskilde by the pope. Instead, Petrus Gervasii found other Dominican helpers. His quite detailed accounts indicate that on several occasions he took local Friars Preachers - especially from Roskilde - in his paid service, often as messengers to the bishops in Jutland. Also, his main bases of residence during the year-long stay in Denmark appear to be the Dominican priories in Roskilde and Lund. At the end of the expedition, the prior of the Preachers in Roskilde and a local Augustinian abbot were each entrusted with half of the sum of money that had been collected. They were to transport it secretly to the harbour of Helsingborg (in Scania) during the winter of 1333-34. In recognition of their help, the Dominican prior was given five solidos grossorum tournois, while the community received a barrel of beer.[43] Apparently, the friars of Roskilde had served the nuncio so well that a Frater Magnus of Roskilde in 1358 was chosen to assist the papal collector Johannes Guilberti during his attempt to bring the Norwegian bishops to pay their debts to the Curia.[44]

A special consideration of the Friars Preachers in Roskilde had to do with the neighbouring Dominican nunnery of St. Agnes, situated just outside the Roskilde city wall. The relation between the two Dominican convents of the First and the Second Order is somewhat ambiguous. Formally, it was the provincial prior and not the prior in Roskilde who was responsible for the nunnery and who was to represent its interests - together with the local bishop - towards the outside world. Furthermore, a lay superintendent was appointed to deal with manorial matters, for instance by representing the sisters at provincial courts. Nevertheless, priors of the friars’ convent in Roskilde occur several times as neutral witnesses or even as appointed advocates on behalf of their Dominican sisters in letters, meetings, and trials. The need to defend the sisters was especially evident in the first half century of the nunnery’s existence due to a notorious scandal created by two young princesses, Agnes and Jutta, who joined the convent in its founding years during the 1260s and brought with them huge estates, but soon regretted their choice and abandoned the convent without permission - taking their landed property with them.[45] For the next sixty years, both the Roskilde priors and the priors provincial had to fight in court to get the royal holdings back from the princesses and their heirs.

Fortunately, the consequences for the Dominican friars of having the St. Agnes Nunnery in their neighbourhood were not all negative. While everything still was harmonious between the Order of Preachers and Princess Agnes, the official initiation of the princess and two other women took place in the friars’ church in 1263. In 1325, the sisters of course had gotten a church of their own, but this did not mean that their need for help from the local brethren was over. This year, we are told, a noble maiden, Christine Jonsdatter, made her vows before the prioress in St. Agnes Church during the Easter high mass, and witnessing all this was a lector from the friars’ convent in Roskilde, while another Dominican frater »..dressed in vestments solemnly read the Gospel during the Mass«.[46] In general, we can assume that ordained friars of the Roskilde Dominicans took care of all pastoral functions required by the sisters in their everyday life, and that the friars’ convent of St. Catherine also was represented at special occasions at St. Agnes by either the prior or a lector.

From several Dominican priories in medieval Denmark, we know that priory buildings could be used for rather non-Dominican purposes, such as lay meetings of various kinds. Such instances are almost completely absent for Roskilde. The only two cases are rather unusual, as they both involve King Christian I and are of a solemn nature. In 1453, the newly appointed Bishop Jakob Friis of Börglum officially gave up his rights to a parish church to a royal representative. This took place in the Dominican priory, in the prior’s chambers. The next day, King Christian himself was present when the Börglum bishop took a pledge of loyalty to the king in the chancel of the Dominican church.[47] The priory was visited by King Christian again in 1466, and this time he brought along his entire council, including Bishop Oluf of Roskilde. Once again, the meeting apparently had nothing to do with the friars themselves.[48] The letters do not explain why these events took place in the Preachers’ priory, but most likely it has to do with a severe city fire which destroyed most of Roskilde in 1443, including the cathedral and large parts of the cathedral chapter, but spared the priory.[49] During the rebuilding of Zealand’s episcopal centre in the following decades, the Dominican priory thus appears to have functioned as a ‘vice-cathedral’ and royal meeting-place.

The Dominican priory in Roskilde during and after the Lutheran Reformation

The convent in Roskilde was one of the last Scandinavian bases of the Order of Preachers during the age of the Lutheran Reformation. In Denmark, Protestant ideas first gained foothold in Jutland, where mendicant priories were forced to close from the late 1520s. Probably, convents on Zealand and in Scania in these years received Dominican ‘refugees’ from other convents of the Nordic province, until also the major east Danish priories had to be abandoned. There are, however, only two extant letters concerning the Roskilde Preachers from this period. As already mentioned, the prior of Roskilde in 1532 was forced to sell the convent’s house in Slagelse »..due to our great need, poverty and destitution.« The house was sold to a local parish priest near Slagelse on the condition that the friars could buy it back if times should change for the better.[50] Seen from a Dominican perspective, the following years did not bring any improvements. In 1536, the Lutheran King Christian III defeated the last of his military, political, and religious opponents, and in the following year, he totally prohibited mendicant orders in Denmark. After this final dissolution, the outgoing provincial prior Dr. Hans Nielsen in 1537 was given a receipt from the Crown for some fine decorated copes and other liturgical vestments taken from the Dominican churches in Lund, Helsingborg, and Roskilde.[51]

After the departure of the friars, the priory in Roskilde seems to have lain waste for some years. Whether or not the town at first found any use for the priory buildings is not clear, but a large part of the priory garden was sold in 1543 by the Crown to royal governor Magnus Godske,[52] and in 1557, the town magistrate received a royal order to »..immediately tear down Blackfriar Priory and Church in Roskilde, which stand deserted.«[53] In the following years, we can follow how the demolition went ahead, as the town recorder in 1559-60 was told to sell bricks from the priory to some local magnates for their manors.[54] In 1565, the demolition of the priory appears to be completed, as nobleman Magnus Godske, who already owned the garden, now received the Crown’s letter on »..a deserted Site in Roskilde, where Blackfriar Priory has stood...«.[55] However, in 1670, remnants of the priory still could be seen in the area.

Even though many bricks from the Dominican priory in Roskilde were sold and reused for manorial buildings outside the town, some of them are probably still to be found. When Magnus Godske became owner of the whole priory site in 1565, he began constructing a manor house called Sortebrödregaard (“Blackfriar Manor”), and according to local city historian Arthur Fang, several bricks showing signs of earlier use can be seen in the present walls.[56] In the final years of the seventeenth century, the manor was bought by two noble widows, who in 1699 founded Roskilde adelige Jomfrukloster (“Roskilde Convent for Noble Maidens”), a home for unmarried women of the higher social classes, and the first of its kind in Lutheran Denmark. And so, the old Dominican priory site in Roskilde still houses a convent, at least nominally speaking. The eastern part of the site was, however, sold off for the construction of a public library in the 1960s; probably not the worst use for the former Dominican gardens, if the learned Friars Preachers of the Middle Ages were to have their say.

Present-day ‘Roskilde Kloster’, formerly known as the ‘Roskilde Convent for Noble Maidens’, seen from the south west. The medieval Dominican priory was situated a little further to the north west. Some of the priory bricks are, however, still to be found as reused material in the new, post-medieval buildings. Photo in van Deurs 1999, 5.

Archaeological findings

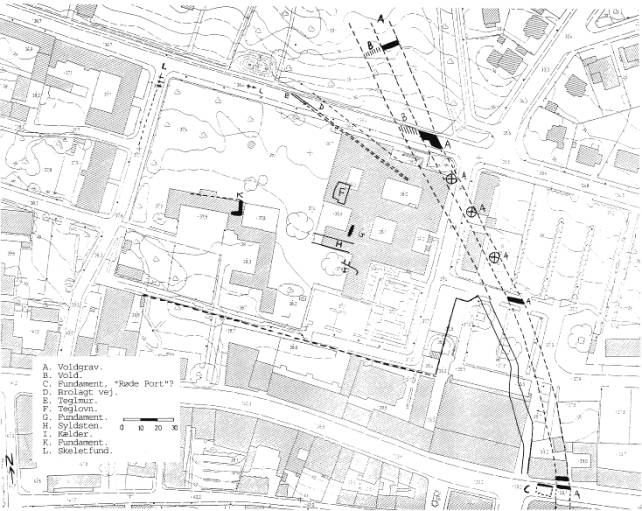

No large-scale or systematic archaeological survey has ever been carried out on the Dominican priory site in Roskilde. In 1891, several skeletons were found under a tile floor in the northern part of the present-day alley St. Pederstræde, which might indicate the location of the priory church or a cloister walk. A few years earlier, remnants of buildings were found in the small garden north of the present-day cloister, and in 1906, some archaeological diggings were conducted in this area, which led to the discovery of a corner from one of the priory buildings, together with remnants of church windows. The findings have, however, been far from sufficient to say anything about the form or size of the priory.[57] Minor excavations on the priory site to the east of the actual priory were performed in 1959 and 1996, and they have established the location of the priory wall and a paved road running along the priory wall between this and the north-eastern city wall.[58] Prior to an extension of the public library in the 1970s, test excavations were performed east of the supposed priory area, and here the archaeologists found remnants of a brick-built cellar and a tile kiln, both medieval.[59]

Map of archaeological findings in and around the Dominican priory site in Roskilde. The markings A and B represent the city wall (B) with an adjoining moat (A). D is the paved road running along the outside of the priory wall (E). F marks the spot, where the tile kiln was found, while I (the curly dot under H) marks the brick-layed cellar. The building corner of the supposed priory is the one marked K, and the general, but unverified thesis is that this might also mark the south-eastern corner of the priory complex - and according to my personal thesis, either the eastern part of the priory church or the southern part of the eastern wing. Dots marked L in the roads to the west and north represent findings of medieval graves. Drawing by Marian Gudsøe in Andersen 1997, 23.

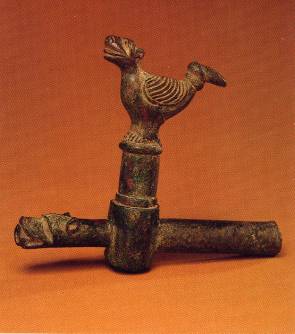

Furthermore, every now and then pieces of medieval building material or various objects have come to surface on the priory site. Besides the often mentioned tombstone of Frater Rano, the most interesting find is a brass tap with its mouth in shape of a dragon’s head and a handle in the shape of a basilisk. Are we perhaps dealing with the “silver dragon” (draconem argenteum) donated by Countess Ingerd to the Dominican convent in 1257? However that may be, it is believed that the combined dragon and basilisk were used by the friars to tap beer. According to Danish folklore tradition, basilisks could emerge in barrels of beer which had gone flat, and then one could hear them flip their tails inside the barrel. So perhaps the little fellow has served as a reminder to the friars to get the barrel emptied before it was too late?

Notes and references:

[1] »1231. Predicatores uenerunt Roskildis. 1234. Missus est conuentus fratrum predicatorum Roskildis.« Annales Petri Olavi, in: Scriptores Rerum Danicarum vol. I, Copenhagen 1772, 183-184. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[2] Also another Franciscan source, Annales Visbyenses, mentions the foundation of a Dominican convent in Roskilde: »1231. Predicatores uenerunt Roskildis.« in: Annales Danici medii ævi (AD), Copenhagen 1920, 137. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis] Indeed, this is the only convent foundation (Dominican or Franciscan) noted in the Annales Visbyenses, which is dated to c.1415, but seems to be based on lost Danish annals of an earlier date. None of the extant thirteenth-century Dominican annals mentions the foundation in Roskilde.

[3] »1232. obiit Johannes, marscalcus Regis Waldemari, filius Ebbonis, in terra sancta in Achon, & sepultus est in Cimiterio b. Nicolai, qvi contulit fratribus Predicatoribus Roskildis ad ecclesiam & claustrum construendum qvadraginta marchas puri argenti.« Annales Petri Olavi, 183. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[4] »1254. Dedicacio ecclesie sancte Katarine fratrum predicatorum Roskildis.« Annales Petri Olavi, 185. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[5] »..pro reparatione ecclesie et emendatione mense 100 marcas puri argenti, et pro reparatione claustri 60 marchas puri argenti…« Annales Petri Olavi, 191. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[6] »Acta sunt hec Roskildis etc., in camera prioris conventus predicatorum ibid.« Repertorium diplomaticum regni danici medii aevi (Repertorium), Copenhagen 1894-1939, 2. ser. vol. I no. 246.

[7] Danske Kancelli-Registranter 1535-50 (“Records of the Danish Chancellery”), Copenhagen 1881-82, 77.

[8] Repertorium 1. ser. vol. III no. 7194.

[9] A recent study of the Danish Franciscans shows that brickworks also were quite common at their priories, and especially in Ribe (western Jutland, Denmark) there are strong indications that Franciscan friars manufactured more bricks than they could use themselves. Jørgen Nybo Rasmussen, Die Franziskaner in den nordischen Ländern im Mittelalter, Kevelaer 2002, 302.

[10] Danske Magazin, Copenhagen 1745 ff., 4. ser. vol. I, 3-4.

[11] Diplomatarium Danicum , Copenhagen 1938 ff., 4. ser. vol. II no. 63.

[12] Rasmussen 2002, 291-292. The Franciscans in Bergen (Norway) even grew exotic fruits like fig and grapes.

[13] The history of the St. Agnes Nunnery in Roskilde will be presented in a separate article at a later time.

[14] Kancelliets Brevbøger (“Letter Books of the Chancellery”), Copenhagen 1885 ff., vol. VIII, 167.

[15] Just like the Dominicans, however, the Franciscans are known to have had a house (a domus terminari?) in Slagelse, which they sold in 1521. Rasmussen 2002, 417.

[16] H. Behrmann, Grundrids til en historisk-topographisk Beskrivelse af det gamle Konge- og Bispesæde Roeskilde, Copenhagen 1832, 209.

[17] »..prior Roskildensis frater Olaus factus est prior prouincialis ibidem.« Annales 980-1286, in: AD, 194. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[18] »..frater P. de Rusquillis, qui successit fratri Oliuero...«. Bernardi Guidonis Historia Ordinis Dominicanorum, Scandinavian content in: K.H. Karlsson, Handlinger rörande Dominikaner-Provinsen Dacia, Stockholm 1901, 6. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[19] Peder Hansen Resen, Atlas Danicus. Roskilde, Copenhagen 1674/1929, 73.

[20] Jarl Gallén, La Province de Dacie de l’ordre des Frères Prêcheurs 1 - Histoire générale jusqu’au Grand Schisme, Helsingfors 1946, 26.

[21]With the Nordic Franciscans, for whom almost all provincial chapters in the Middle Ages are registered, 11 meetings took place in Roskilde. Until 1490, the convent in Roskilde housed a provincial chapter about every thirtieth year. For comparison, it should be remembered that the Franciscan province of Dacia counted 48 medieval convents, whereas the Dominicans reached a total of 31. Rasmussen 2002, 518-534.

[22] Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. VII no. 291. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[23] Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. II no. 86. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[24] »Honorabilis Vir Dominus Petrus, dictus Brackæ, Curatus Ecclesiæ Broby (…). Qvi tandem, relictis omnibus, ad Fratres Ordinis Prædicatorum transmigravit Roskildis.« Sorø Donation Book, in: Scriptores Rerum Danicarum vol. IV, Copenhagen 1776, 463-531. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[25] »Item fratribus predicatoribus Roschildis xx marcas denar. (…) Item fratribus predicatoribus Roschildis draconem argenteum et pixidem.« Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. I no. 240. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[26] »Ingeburgis, ducissa Suecie, Hallandie, Holbec, Samsiø 1330 et 1336 dedit fratribus predicatoribus Roskildis in testamento pro reparatione ecclesie et emendatione mense 100 marcas puri argenti..« Annales Petri Olavi, 191. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[27] »..et pro reparatione claustri 60 marchas puri argenti anno Domini 1350.« Annales Petri Olavi, 191. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[28] »Sorores insuper ad infrascripta erunt obligate (...) conuentui Roskildensi ordinis predicatorum singulis personis annis sex solidos grossorum Turonensium pro lampade eorum in choro sustentando soluere perpetuo teneantur.« Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. VI no. 93.

[29] Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. V no. 40. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[30] Danske Magazin 3. ser. vol. III, 297, and Diplomatarium diocesis Lundensis, Lund 1900-1939, vol. VI no. 203.

[31] Diplomatarium Danicum 3. ser. vol. III no. 285, Danske Magazin 3. ser. vol. III, 213-219, Repertorium 1. ser. no. 5936 and no. 6703, and Repertorium 2. ser. vol. IV no. 6776.

[32] Diplomatarium Danicum 4. ser. vol. VIII no. 459.

[33] In the original version of this article (as printed in DHN vol. 14), the numbers were slightly different (85% nobility and 12% clergy), but in the meantime, I have registered eight more donations, which have changed the statistics.

[34] Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. IV no. 27 [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis], and Repertorium 1. ser. no. 6890.

[35] In all fairness it should be added that no will has been preserved from his predecessor the Dominican Bishop Johannes Nyborg (†1344); in all likelihood, he too must be expected to have included the friars in his final will.

[36] Diplomatarium Danicum 3. ser. vol. III no. 285. The mentioned collection of sermons has been indentified as De tempore et de sanctis by Jacobi de Losanna.

[37] »Item Twæ Ipssøn, cocus in ordine predicatorum, solvit totum preter gerdh.« Danmarks Gilde- og Lavsskraaer fra Middelalderen vol. 1, Copenhagen 1895, 367.

[38] Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. I no. 461. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[39] Repertorium 1. ser. vol. III no. 7850.

[40] Repertorium 2. ser. vol. I no. 47.

[41] Repertorium 1. ser. vol. III no. 7400.

[42] Acta processus litium - inter regem danorum et archiepiscopum lundensem, Copenhagen 1932, 13. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[43] Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. XI no. 152. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[44] Diplomatarium Norvegicum, Christiania/Oslo 1849-1976, vol. VIII no. 168 and 173.

[45] The whole case is thoroughly described by Jarl Gallén 1946, 89-99.

[46] Diplomatarium Danicum 2. ser. vol. IX no. 181. [Diplomatarium OP Roskildensis]

[47] Repertorium 2. ser. vol. I no. 246.

[48] Repertorium 2. ser. vol. I no. 2165.

[49] Liber daticus Roskildensis, Copenhagen 1933, 110.

[50] Danske Magazin 1. ser. vol. II, 157-158.

[51] Danske Kancelli-Registranter 1535-50, 58.

[52] Danske Magazin 4. ser. vol. I, 3-4.

[53] Letter Books of the Chancellery vol. II, 62.

[54] Letter Books of the Chancellery vol. II, 255 and 372.

[55] Letter Books of the Chancellery vol. III, 597.

[56] Arthur Fang, Roskilde - Fra byen og dens historie vol. 1, Roskilde 1945, 317.

[57] Archaeological reports for the National Museum of Denmark by Jacob Kornerup 1891 and C.M. Schmidt 1906. The reports are unpublished, but the main results are referred in: Vilhelm Lorenzen, De danske Dominikanerklostres Bygningshistorie, Copenhagen 1920, 57; E. Moltke et al., Danmarks Kirker - Københavns Amt vol. 1, Copenhagen 1944, 159; Piet van Deurs, Roskilde Kloster, Roskilde 1999, 10-11.

[58] Archaeological reports by Ole Feldbæk 1959 (in: van Deurs 1999, 11-12) and Jens Andersen 1996 (in: Jens Andersen, ‘Byvold og klostermur - arkæologisk undersøgelse i Dronning Margrethes Vej 1996’, in ROMU - Årsskrift fra Roskilde Museum 1996, Roskilde 1997, 25-28.

[59] Archaeological reports by Olaf Olsen 1973-74 (in: Andersen 1997, 25) and Morten Aaman Sørensen 1978 (in: Andersen 1997, 25).

Centre

for Dominican Studies of Dacia

Johnny

G.G. Jakobsen, Department of Scandinavian Research, University of Copenhagen

Postal address: Njalsgade 136, DK-2300 Copenhagen, Denmark ● Email: jggj@hum.ku.dk